What happens behind vllm serve

vLLM is what first sparked my interest in LLM deployment – although it was not the first framework I used. I actually started out with TGI, running in a dedicated container on AWS Sagemaker. vLLM, however, quickly became my go-to solution for serving LLM, mainly because of its performance and ease of use.

In a previous peek, I covered the basics of modern LLM serving frameworks. At their core are the concepts of LLM engine and LLM server. That earlier post just scratched the surface. In this one, I will take a much deeper dive and we will see how these are actually implemented in vLLM.

How to use vLLM’s engine?

I previously discussed how vLLM’s main optimizations come from its engine. It can be instantiated and used offline on its own.

from vllm import LLM

llm = LLM(model="mistralai/Mistral-Small-3.1-24B-Instruct-2503") # path to the model repository in Hugging Face Hub

Initialize a vLLM engine for Mistral Small 3.1

This is not how I have been using vLLM in practice. For a full serving experience, you can run the engine within an inference server that mimics the OpenAI API protocol.

vllm serve mistralai/Mistral-Small-3.1-24B-Instruct-2503

Serves a vLLM engine for Mistral Small 3.1 with OpenAI API protocol

This is how I have been using vLLM. This command spins up a FastAPI server that makes the engine available for online inference. As you can see, the command is very straightforward – just run it on a capable machine (ideally with a GPU) and you are good to go (at least for prototyping).

This simplicity masks the optimizations implemented under the hood. You might be using vLLM without even realizing it – like I was. So, what is really going on behind vllm serve?

This post is divided into two parts

- `vllm serve` walkthrough is a step-by-step walk through the code of vLLM from the command execution to the core components

- Understanding vLLM optimizations is an in-depth explanation of the theory behind the optimizations of vLLM

The parts are largely independent

vllm serve workflow

Starting the server

Let’s start from the above command a user would run in its terminal:

vllm serve mistralai/Mistral-Small-3.1-24B-Instruct-2503

The command calls a script that relies on vllm CLI. This script is defined in vllm/pyproject.toml at the root of the repository. This kind of file is used with popular project management tools like Poetry to act as a central configuration for settings, dependencies, scripts, and more.

pyproject.toml41 [project.scripts]

42 vllm = "vllm.entrypoints.cli.main:main"The entrypoint is in vllm/vllm/entrypoints/cli/main.py which is a dispatch for the subcommands of the command line (serve, openai, benchmark.main, collect_env). The user command would run the serve subcommand with the positional argument 'mistralai/Mistral-Small-3.1-24B-Instruct-2503'.

vllm/entrypoints/cli/serve.py...

8 from vllm.entrypoints.openai.api_server import run_server

...

14 class ServeSubcommand(CLISubcommand):

15 """The `serve` subcommand for the vLLM CLI. """

16

17 def __init__(self):

18 self.name = "serve"

19 super().__init__()

20

21 @staticmethod

22 def cmd(args: argparse.Namespace) -> None:

23 # If model is specified in CLI (as positional arg), it takes precedence

24 if hasattr(args, 'model_tag') and args.model_tag is not None:

25 args.model = args.model_tag

26

27 uvloop.run(run_server(args))It passes the argument to a run_server function which runs in an asyncio event loop. This function essentially builds a FastAPI application and injects the core components of vLLM in its state.

vllm/entrypoints/openai/api_server.py1041 async def run_server(args, **uvicorn_kwargs) -> None:

...

1077 async with build_async_engine_client(args) as engine_client:

1078 app = build_app(args)

1079

1080 vllm_config = await engine_client.get_vllm_config()

1081 await init_app_state(engine_client, vllm_config, app.state, args)

...The core logic is implemented in the engine client. It is an asynchronous client provided in a context manager. Following the stack trace, it is initialized in the build_async_engine_client function, which essentially calls the build_async_engine_client_from_engine_args function of the same file.

vllm/entrypoints/openai/api_server.py138 @asynccontextmanager

139 async def build_async_engine_client(

140 args: Namespace) -> AsyncIterator[EngineClient]:

141

142 # Context manager to handle engine_client lifecycle

143 # Ensures everything is shutdown and cleaned up on error/exit

144 engine_args = AsyncEngineArgs.from_cli_args(args)

145

146 async with build_async_engine_client_from_engine_args(

147 engine_args, args.disable_frontend_multiprocessing) as engine:

148 yield engine

149

150

151 @asynccontextmanager

152 async def build_async_engine_client_from_engine_args(

153 engine_args: AsyncEngineArgs,

154 disable_frontend_multiprocessing: bool = False,

155 ) -> AsyncIterator[EngineClient]:

...

168 # V1 AsyncLLM.

169 if envs.VLLM_USE_V1:

...

177 try:

178 async_llm = AsyncLLM.from_vllm_config(

179 vllm_config=vllm_config,

180 usage_context=usage_context,

181 disable_log_requests=engine_args.disable_log_requests,

182 disable_log_stats=engine_args.disable_log_stats)

183 yield async_llm

...

188 # V0 AsyncLLM.

189 elif (MQLLMEngineClient.is_unsupported_config(vllm_config)

190 or disable_frontend_multiprocessing):

191

...

193 try:

194 engine_client = AsyncLLMEngine.from_vllm_config(

195 vllm_config=vllm_config,

196 usage_context=usage_context,

197 disable_log_requests=engine_args.disable_log_requests,

198 disable_log_stats=engine_args.disable_log_stats)

199 yield engine_clientvLLM V1 released its alpha in January 2025 and introduces significant upgrades which are beyond the scope of this post. As of the date I am writing this, April 2025, we assume the user has already switched to vLLM V1. So the engine client here is an instance of AsyncLLM.

AsyncLLM may take some time to initialize, the server will start as soon as it is ready. Let’s dig in its initialization process to understand the heavy lifting happening in there.

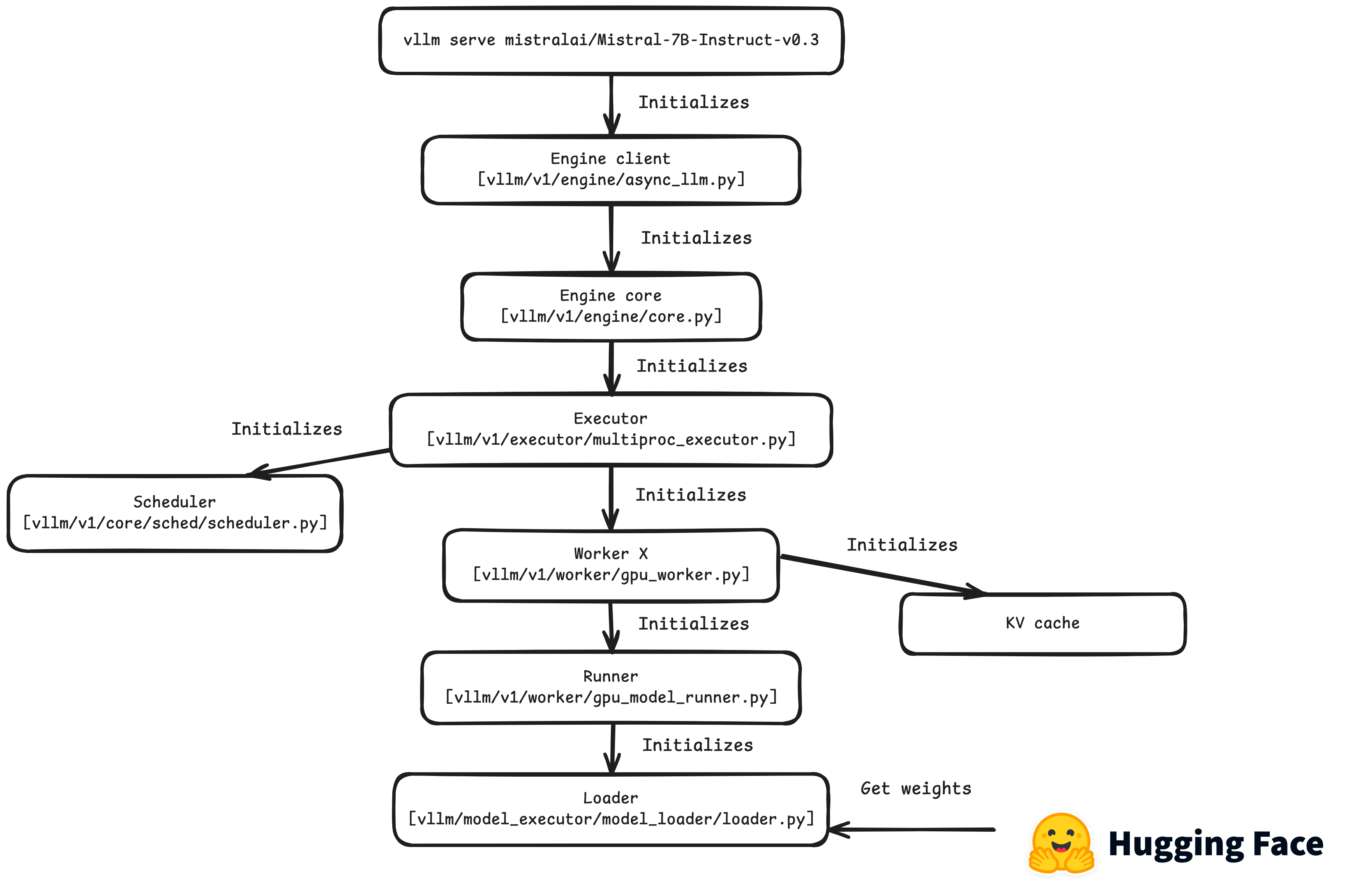

Initializing the engine

AsyncLLM is a client which wraps the core engine of vLLM. Its core attribute is the engine_core which is an instance of AsyncMPClient. This object creates a CoreEngine which will run an EngineCore in a background process. The EngineCore is the main component of vLLM, as its name suggests.

vllm/v1/engine/core.py47 class EngineCore:

48 """Inner loop of vLLM's Engine."""

49

50 def __init__(self,

51 vllm_config: VllmConfig,

52 executor_class: type[Executor],

53 log_stats: bool,

54 executor_fail_callback: Optional[Callable] = None):

55 assert vllm_config.model_config.runner_type != "pooling"

56

57 logger.info("Initializing a V1 LLM engine (v%s) with config: %s",

58 VLLM_VERSION, vllm_config)

59

60 self.log_stats = log_stats

61

62 # Setup Model.

63 self.model_executor = executor_class(vllm_config)

64 if executor_fail_callback is not None:

65 self.model_executor.register_failure_callback(

66 executor_fail_callback)

67

68 # Setup KV Caches and update CacheConfig after profiling.

69 num_gpu_blocks, num_cpu_blocks, kv_cache_config = \

70 self._initialize_kv_caches(vllm_config)

71

72 vllm_config.cache_config.num_gpu_blocks = num_gpu_blocks

73 vllm_config.cache_config.num_cpu_blocks = num_cpu_blocks

74

75 self.structured_output_manager = StructuredOutputManager(vllm_config)

76

77 # Setup scheduler.

78 if isinstance(vllm_config.scheduler_config.scheduler_cls, str):

79 Scheduler = resolve_obj_by_qualname(

80 vllm_config.scheduler_config.scheduler_cls)

81 else:

82 Scheduler = vllm_config.scheduler_config.scheduler_cls

83

84 # This warning can be removed once the V1 Scheduler interface is

85 # finalized and we can maintain support for scheduler classes that

86 # implement it

87 if Scheduler is not V1Scheduler:

88 logger.warning(

89 "Using configured V1 scheduler class %s. "

90 "This scheduler interface is not public and "

91 "compatibility may not be maintained.",

92 vllm_config.scheduler_config.scheduler_cls)

93

94 self.scheduler: SchedulerInterface = Scheduler(

95 scheduler_config=vllm_config.scheduler_config,

96 model_config=vllm_config.model_config,

97 cache_config=vllm_config.cache_config,

98 lora_config=vllm_config.lora_config,

99 kv_cache_config=kv_cache_config,

100 speculative_config=vllm_config.speculative_config,

101 structured_output_manager=self.structured_output_manager,

102 include_finished_set=vllm_config.parallel_config.data_parallel_size

103 > 1,

104 log_stats=self.log_stats,

105 )

106

107 # Setup MM Input Mapper.

108 self.mm_input_cache_server = MirroredProcessingCache(

109 vllm_config.model_config)

110

111 # Setup batch queue for pipeline parallelism.

112 # Batch queue for scheduled batches. This enables us to asynchronously

113 # schedule and execute batches, and is required by pipeline parallelism

114 # to eliminate pipeline bubbles.

115 self.batch_queue_size = self.model_executor.max_concurrent_batches

116 self.batch_queue: Optional[queue.Queue[tuple[Future[ModelRunnerOutput],

117 SchedulerOutput]]] = None

118 if self.batch_queue_size > 1:

119 logger.info("Batch queue is enabled with size %d",

120 self.batch_queue_size)

121 self.batch_queue = queue.Queue(self.batch_queue_size)A lot is happening during initialization, among which the KV cache and scheduler setup. We will talk about these later, as they are vLLM’s key optimizations.

The EngineCore requires an executor to actually run the model. The executor subclass depends on the number of GPUs available on the user’s machine and their configuration. The executor is in charge of setting up the workers on the device.

The default for one GPU is a UniProcExecutor. For several GPUs on one node (one machine), the executor class is MultiProcExecutor. Then, for several nodes, required for very large models like Mixtral 8x22B (~280G), it would resort to a RayDistributedExecutor. In our case the model weights are about 50GB, so the user should better run it on a machine with several GPUs, or one A100 80G (it would fit yet be a bit tight). Let’s assume the user has several A10G GPUs, hence vLLM would use a MultiProcExecutor.

Assuming the user runs the command on a machine with several GPUs, the executor will start several instances of GPUWorker, one for each GPU. Each worker requires a runner for the model, in this case a GPUModelRunner. The runner starts by loading the model on the device thanks to a model loader.

Now, several implementations of the model loader are defined depending on the format of the model weights (DummyModelLoader, TensorizerLoader, ShardedStateLoader, BitsAndBytesModelLoader, GGUFModelLoader, RunaiModelStreamerLoader, ShardedStateLoader, DefaultModelLoader). The appropriate one will be selected depending on the user’s choice and configuration, in the get_model_loader function.

Let’s assume the user does not have a specific configuration and runs the command without any other argument. Hence, the loader will be DefaultModelLoader. It will get the model path passed in the CLI parameters 'mistralai/Mistral-Small-3.1-24B-Instruct-2503'. Assuming again that this is the first time the user runs this command on the machine, the loader will download the model weights from Hugging Face Hub (download_weights_from_hf). It will perform a direct API call via the snapshot_download function of huggingface_hub library to get the weights.

The download may take a while depending on the model and the user’s bandwidth. In this case, Mistral-Small-3.1-24B-Instruct-2503 represents about 50GB of safetensors weights. Once the download is complete, the weights will be stored in this folder ~/.cache/huggingface/hub/Mistral-Small-3.1-24B-Instruct-2503 on the machine for faster initializations in the future. The worker will then load the weights on the GPU.

Once the workers are ready, and the core components of the engine are setup, the server will finally start to accept incoming requests.

Figure 1. Call stack for vllm engine initialization. Hugging Face ® is a trademark of Hugging Face Inc. This blog is not affiliated or sponsored by Hugging Face.

Figure 1. Call stack for vllm engine initialization. Hugging Face ® is a trademark of Hugging Face Inc. This blog is not affiliated or sponsored by Hugging Face.

Requesting the server

vLLM’s server exposes several routes, which are all defined in a router object bound to the FastAPI application at launch. The user could directly request the LLM by running a command in terminal.

# Using the v1/completions route

curl http://localhost:8000/v1/completions \

-H "Content-Type: application/json" \

-d '{

"model": "mistralai/Mistral-Small-3.1-24B-Instruct-2503",

"prompt": "The capital of Peru is",

}'

# Using the v1/chat/completions route

curl http://localhost:8000/v1/chat/completions \

-H "Content-Type: application/json" \

-d '{

"model": "mistralai/Mistral-Small-3.1-24B-Instruct-2503",

"messages": [

{"role": "system", "content": "You tell the capitals of countries."},

{"role": "user", "content": "What is the capital of Peru?"}

]

}'

For a chatbot that keeps a conversation history for dynamic conversations, you would now use the v1/chat/completions route. However, the curl command is a bit verbose and it would be tedious to pass the growing conversation history for every new request. So a user would usually rely on a library like openai or a framework like LangChain or LlamaIndex. We will assume that the user builds their application with LangChain, which is very convenient for me as it is the one I know best.

Since, vLLM mimics OpenAI Chat Completions API, it can be used as a drop-in replacement for OpenAI models easily. Assuming the application used the ChatOpenAI object from LangChain, the user would simply need to change the base_url parameter to the URL of the server where vLLM is running.

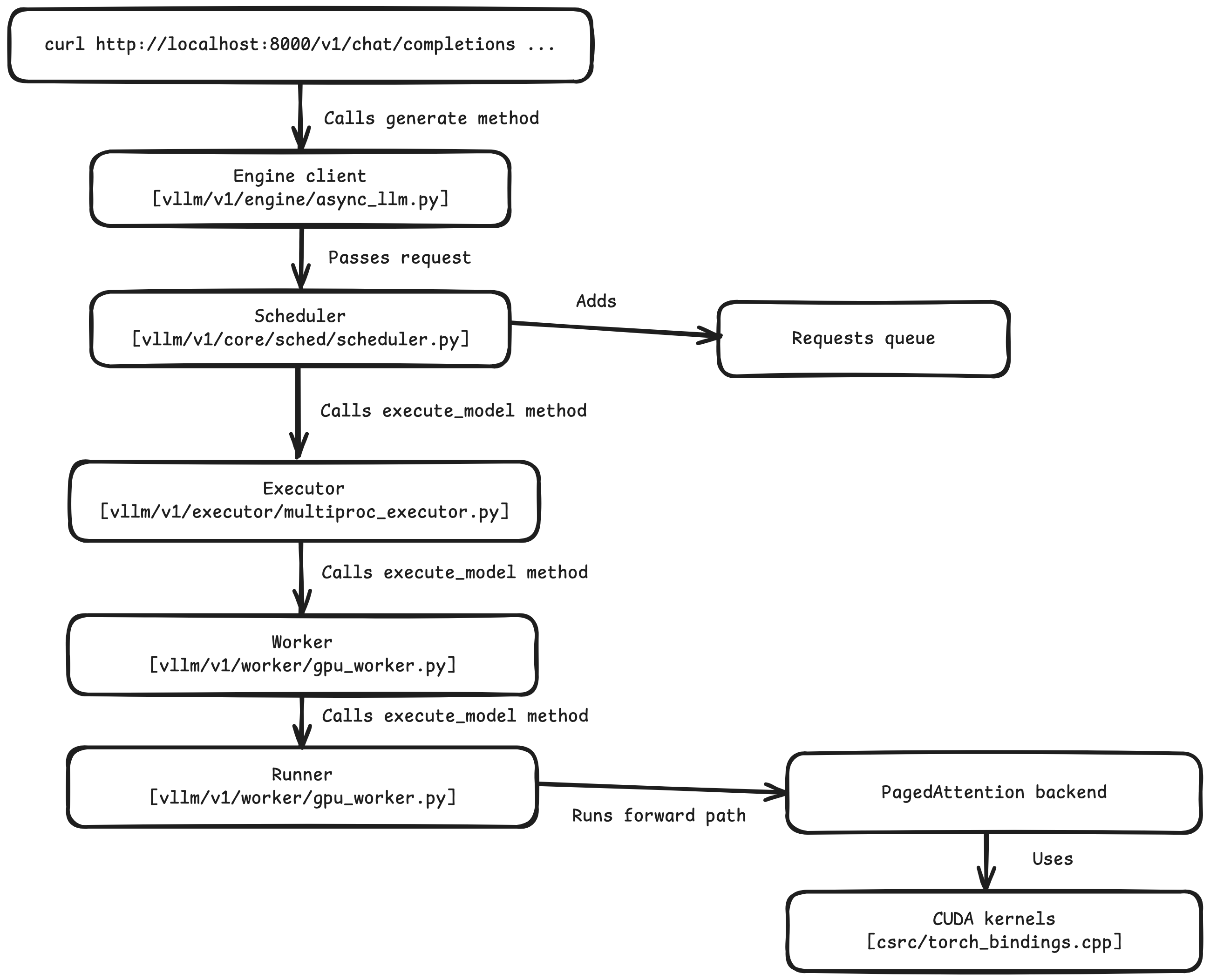

The user’s application is now calling the v1/chat/completions route on vLLM’s server via LangChain. This will call the create_chat_completion function that will return a StreamingResponse. The user will thus receive the output chunk by chunk until completion, which minimizes the wait for interaction.

vllm/entrypoints/openai/api_server.py305 router = APIRouter()

...

466 @router.post("/v1/chat/completions",

467 dependencies=[Depends(validate_json_request)])

468 @with_cancellation

469 @load_aware_call

470 async def create_chat_completion(request: ChatCompletionRequest,

471 raw_request: Request):

472 handler = chat(raw_request)

473 if handler is None:

474 return base(raw_request).create_error_response(

475 message="The model does not support Chat Completions API")

476

477 generator = await handler.create_chat_completion(request, raw_request)

478

479 if isinstance(generator, ErrorResponse):

480 return JSONResponse(content=generator.model_dump(),

481 status_code=generator.code)

482

483 elif isinstance(generator, ChatCompletionResponse):

484 return JSONResponse(content=generator.model_dump())

485

486 return StreamingResponse(content=generator, media_type="text/event-stream") The core logic of generation resides in the engine client that was initialized at launch. It is implemented in the AsyncLLM class. The client leverages the engine core to add the user’s request to the queue. The scheduler then reviews queued requests and schedules them for completion (I will talk about scheduling in the second part of the post).

The executor then passes the request along until the model runner where it is transformed to the model’s expected input format. The GPUModelRunner finally executes the model forward pass with this input. The forward pass happens within a context which sets up the backend for the attention computation. vLLM supports several backends for attention, and selects the most relevant one given the system, hardware, and model specification.

vllm/vllm/v1/worker/gpu_model_runner.py996 @torch.inference_mode()

997 def execute_model(

998 self,

9990 scheduler_output: "SchedulerOutput",

1000 intermediate_tensors: Optional[IntermediateTensors] = None,

1001 ) -> Union[ModelRunnerOutput, torch.Tensor]:

...

1077 # Run the decoder.

1078 # Use persistent buffers for CUDA graphs.

1079 with set_forward_context(attn_metadata, self.vllm_config):

1080 hidden_states = self.model(

1081 input_ids=input_ids,

1082 positions=positions,

1083 intermediate_tensors=intermediate_tensors,

1084 inputs_embeds=inputs_embeds,

1085 )

...Almost all of these backends call the PagedAttention operation when running on supported hardware. PagedAttention was developed by the vLLM’s team to optimize self attention for LLM inference. They defined it as a custom operation and implemented specific CUDA kernels to support it (CUDA kernels are functions that run on NVidia GPUs).

Honestly, this is where things get too technical for me. The CUDA kernels are implemented in csrc/attention/ and the bindings are defined in csrc/torch_bindings.cpp, to be used in the forward context. I expect most people would not need to touch that unless they are looking to optimize low-level logic for a few milli-seconds.

Figure 2. Call stack for vllm generation

Figure 2. Call stack for vllm generation

Understanding vLLM optimizations

KV cache management

In my previous post, I explained how LLM inference is mostly memory-bound. In more detail, generating an answer consists in two phases:

- Prefill-phase (Prompt processing): Compute the attention vectors for each token in the prompt. This phase is actually compute-bound, but fast as it takes advantage of GPU parallelism.

e.g, It is the time before the first token appears in ChatGPT - Decoding phase (Generation): Generate tokens sequentially from the prompt. Computations cannot be run in parallel and the attention vectors for each new token shall be cached to avoid redundant computation at every step. Since the number of such vectors grows linearly with the length of the sequence, this phase is memory-bound. It accounts for most of the latency.

e.g, It is the time from when the first token appears until the answer is complete

Since the decoding phase usually dominates latency, LLM inference is often said to be memory-bound.

During decoding, only the key and value vectors are cached, as previous queries are never re-used. Here is the self attention equation for reference:

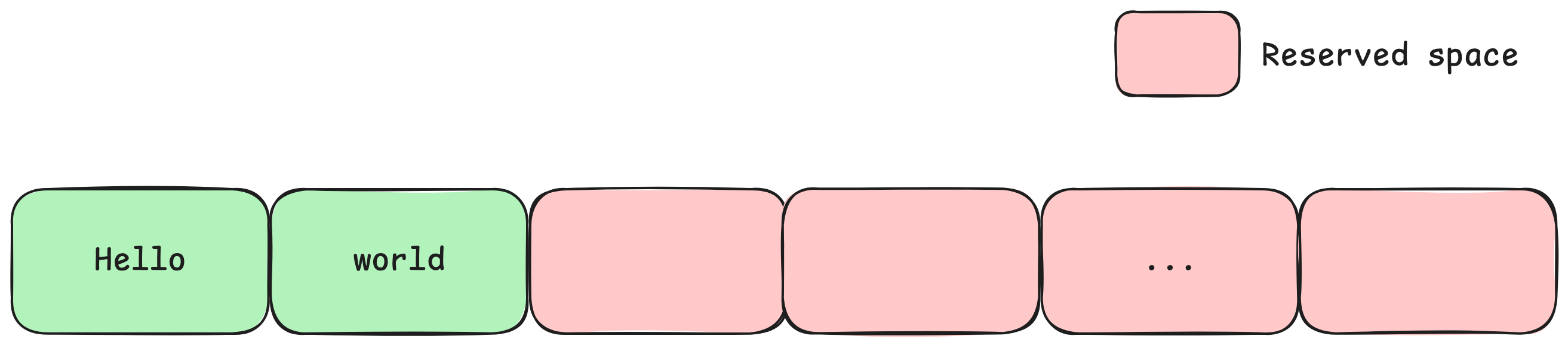

\[\text{Attention}(Q, K, V) = \text{softmax}\left(\frac{QK^\top}{\sqrt{d}}\right)V\]KV cache management is key in improving decoding latency and handling growing sequences. However, there is no way to know in advance how long a sequence will be.

A naïve implementation would try to allocate the maximum memory the LLM would need for a sequence, which is the model’s context window. Since tensor-processing frameworks such as PyTorch require tensors to be contiguous in memory, it would pre-allocate a huge contiguous chunk of GPU RAM.

This would lead to huge memory wastes, as most sequences would never reach the current context windows lengths. These went from usually 2048 tokens in early 2023 open-source models, to up to 1 million now with the latest Llama 4 models. Llama 4 Scout even advertised a 10 million tokens context window, so this naïve approach would not even be feasible, and would scale poorly anyway. Fixed allocation cannot accommodate the dynamic nature of decoding.

vLLM’s KV cache manager

Allocating one large contiguous chunk of memory for a sequence’s KV cache leads to a problem known as internal fragmentation. This means that the majority of the chunk is unused and unavailable to another process.

vLLM solves this by splitting memory into fixed-size blocks. These blocks are small contiguous chunks of memory but not necessarily contiguous to one another. They can hold a fixed number of attention vectors depending on their size (block size is discussed in section 7.2 of the vLLM research paper).

These blocks are allocated on the fly so a sequence only uses the memory it needs, and internal fragmentation is limited to one block.

Figure 3. Example of internal fragmentation. Reserved spaces are unused and unavailable for other sequences

Figure 3. Example of internal fragmentation. Reserved spaces are unused and unavailable for other sequences

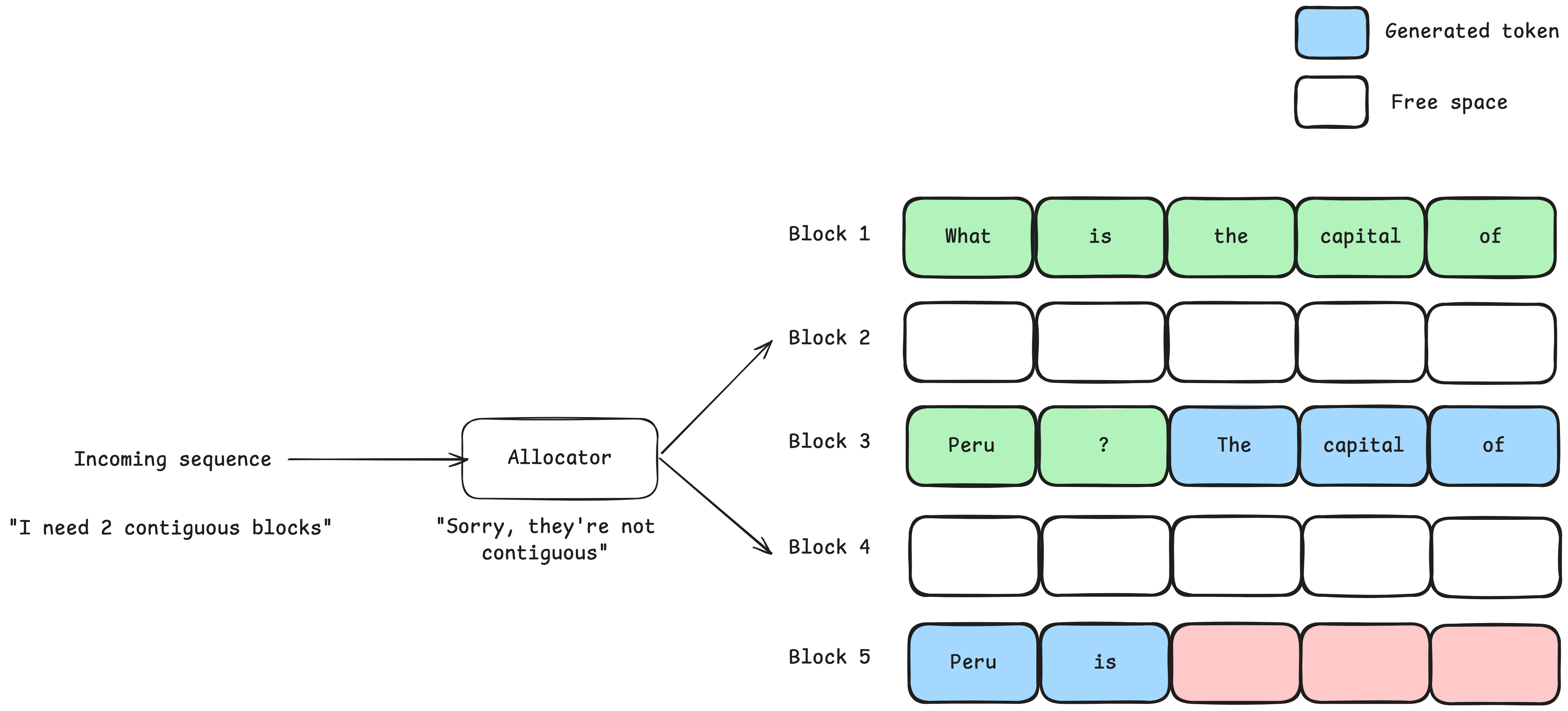

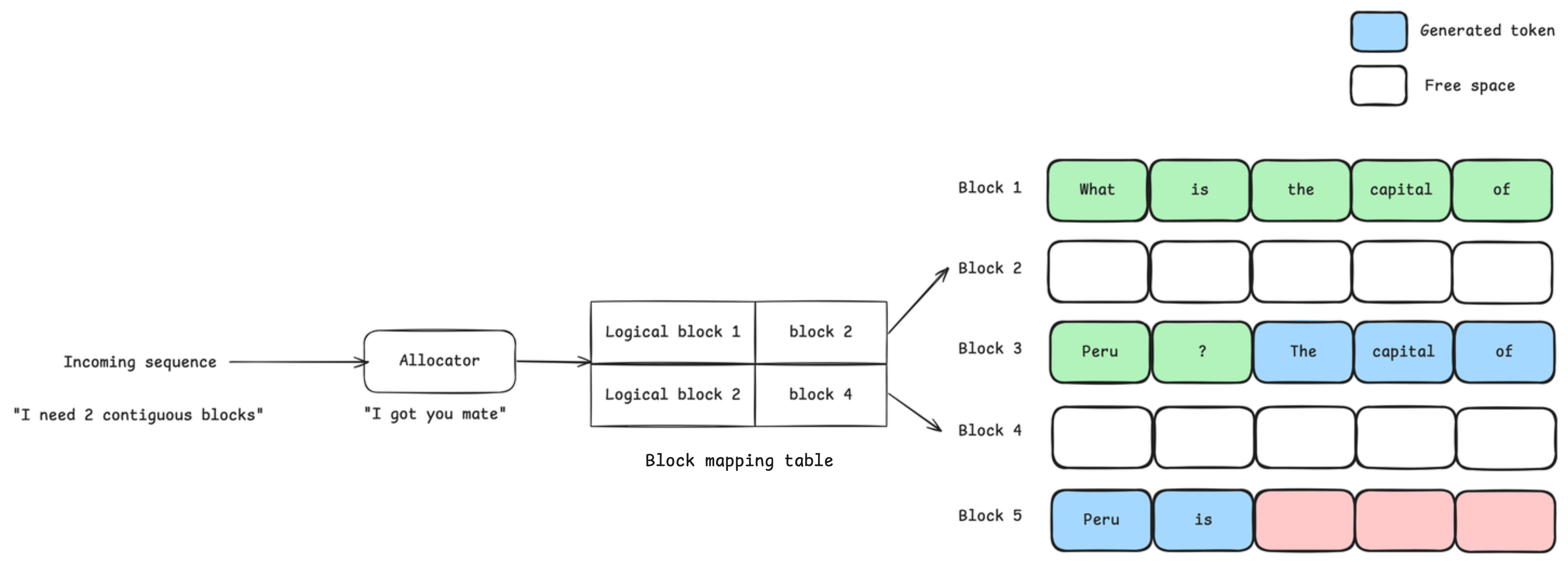

However, blocks are not necessarily contiguous to one another, which would lead to yet another issue known as external fragmentation. This happens when a new incoming sequence asks for memory blocks, yet not enough contiguous blocks are available. So the sequence could not be processed, although there is enough memory available on the GPU. A naïve solution would be to enforce contiguity between blocks but it would not be possible as sequences lengths are not known in advance.

Figure 4. Example of external fragmentation. The allocator cannot provide contiguous blocks although there is enough free memory.

Figure 4. Example of external fragmentation. The allocator cannot provide contiguous blocks although there is enough free memory.

vLLM solves external fragmentation by introducing an indirection with logical-to-physical block mapping. The engine manages a block table for each sequence with contiguous logical blocks. Tensor-processing frameworks would see these blocks which satisfy the contiguity requirement, but no memory is consumed until physical blocks are actually allocated. This is inspired from virtual memory in OS systems.

Figure 5. Logical-to-physical block mapping. The allocator sees logical blocks as contiguous and can allocate them for the incoming sequence.

Figure 5. Logical-to-physical block mapping. The allocator sees logical blocks as contiguous and can allocate them for the incoming sequence.

However, traditional self attention kernels still require tensors to be contiguous in memory, so these could not apply with vLLM’s KV cache management. Hence, vLLM implements PagedAttention, a block-wise rewriting of self attention.

PagedAttention

Let’s go back to the self attention equation and explain what happens during decoding step-by-step.

\[\text{Attention}(Q, K, V) = \text{softmax}\left(\frac{QK^\top}{\sqrt{d}}\right)V\]Imagine we are at decoding step $t$, the current token was sampled from the previous step:

These are the computations for the first layer and one attention head for the sake of simplicity, however it is easily extensible

notations: $d_e$ is the embedding size, $d$ is the projection dimension

- Get the embedding of the current token, $x_t \in \mathbb{R}^{d_e}$.

- Project the embedding to get the current query, key, and value vectors

\(\begin{gather} q_t = W_q x_t \in \mathbb{R}^{d},\\ k_t = W_k x_t \in \mathbb{R}^{d},\\ v_t = W_v x_t \in \mathbb{R}^{d}. \end{gather}\) - Concatenate the current key and value vectors $k_t, v_t$ with previous ones $(k_1,…,k_{t-1})$ and $(v_1,…,v_{t-1})$ retrieved from the KV cache (if there is no KV cache, recompute these). The results are $K_t, V_t \in \mathbb{R}^{t \times d}$.

- Compute the attention scores for the current token $a_t = \text{softmax}\left(\frac{q_t K_t^\top}{\sqrt{d}}\right) \in \mathbb{R}^t$.

- Compute the layer output $o_t = a_t V_t \in \mathbb{R}^d$.

A framework like PyTorch is unable to compute the dot-products of step 4 and 5 on non-contiguous tensors efficiently. So vLLM splits these per block.

Imagine that a block $j$ can hold the key and value vectors of $B$ tokens. You may retrieve $K_j, V_j \in \mathbb{R}^{B \times d}$. Since a block is a contiguous chunk of memory, it is possible to compute the following block-wise dot-product:

The results are accumulated across each block of the sequence to get the denominator of the softmax $S=\sum_{j} \text{exp}\left(\frac{q_t K_j^\top \mathbf{1}}{\sqrt{d}}\right) \in \mathbb{R}$.

I am using the notation from the paper here (section 4.1), but I find it a bit confusing. The denominator is the sum of all exponentials across all blocks. First the partial sums are computed block-wise, and then all summed together to get the sum for the entire sequence.

The all-ones vector $\mathbf{1} \in \mathbb{R}^B$ in the exponential in the paper is misleading, it should actually be $S=\sum_{j} [ \text{exp}\left(\frac{q_t K_j^\top}{\sqrt{d}}\right) \mathbf{1}] \in \mathbb{R}$. This is equivalent to the double sum $S=\sum_{j} \sum_{i}^B [\text{exp}\left(\frac{q_t K_j^\top}{\sqrt{d}}\right)]_i \in \mathbb{R}$.

We would then compute the block-wise attention scores:

Finally, we can compute the dot-product between attention scores and value vectors block-wise, and sum over blocks to get the layer output $o_t$:

\[o_t = \sum_j a_j V_j \in \mathbb{R}^d\]That is what PagedAttention does. It enables to compute self attention while minimizing external and internal fragmentation. This is the key optimization of vLLM. In order to make PagedAttention more efficient, vLLM also developed specific CUDA kernels (previous part and section 5.1 of the vLLM research paper).

Continuous batching

When serving several users, sequences are processed in groups instead of sequentially, to maximize GPU utilization and minimize latency for each user. This approach is very common in machine learning and is known as batching.

Most serving systems use fixed-size batching, e.g, an offline image recognition software. In this case, the outputs are returned once every item in the batch has been processed. However, this is not suited to decoding sequences due to the auto-regressive nature of LLM. Since the output length of a sequence is not known in advance, it could make shorter sequences wait for longer sequences in the batch to finish, leaving the GPU idle and increasing latency.

Although introducing micro-batches of sequences with varying batch size would mitigate the issue, as it would limit it to each micro-batch, it would still not solve the underlying problem.

To tackle this problem, vLLM implements iteration-level scheduling, an approach introduced by Orca. Instead of scheduling entire sequences for processing, vLLM schedules a batch of tokens at each decoding step. The batch size may change depending on incoming traffic, and tokens may come from different sequences between consecutive batches. This enables to return a sequence output directly upon completion, and introduce tokens from another sequence at the next iteration. This approach is a key optimization of vLLM called continuous batching.

The max_num_batched_tokens parameter of the engine defines the budget (or maximum batch size) for each iteration. The engine also has an upper bound on the number of sequences these tokens come from, which is the max_num_seqs parameter.

Now, how does each sequence contribute to this budget?

Remember that LLM inference consists in two steps: prefill (prompt encoding) and decode (output generation). I previously described prefill as the time before the first token appears in ChatGPT. This is actually a metric called TTFT, i.e Time To First Token. Decoding, on the other hand, is the time from first token until completion. The time between each decoding step is called ITL, i.e Inter Token Latency.

At prefill, a sequence may contribute as many tokens as the context window (max_model_len parameter). However, during decoding, each sequence may contribute only one token. By default, vLLM’s scheduler prioritizes prefill, meaning incoming prompts are scheduled before already running sequences and may interrupt decoding. In this case, prefill and decode tokens always run in different batches. This means that vLLM’s default behaviour favours TTFT over ITL.

However, vLLM has recently introduced chunked prefill, which enables to tune the scheduler’s behaviour towards better ITL. When the --enable-chunked-prefill flag is passed to the engine, prompts are split into fixed size chunks of tokens and decoding now takes priority. Prefill and decode tokens may also be mixed in the same batch. This means that at each GPU cycle, tokens from running sequences are scheduled in priority, and chunked prefills may use the remaining budget, if any.

The token budget and chunked prefills size may be tuned to reach a trade-off between TTFT and ITL depending on the developer’s needs.

Among prefill and decoding, vLLM implements a first-in-first-out policy, meaning that older sequences are processed first.

These optimizations have increased the throughput, i.e the number of tokens processed per second on GPU, up to a factor of 23!

Sequence preemption

During surges in traffic, GPU memory may run out and vLLM may not be able to keep the KV cache of all sequences. In that case, it may preempt sequences, i.e evict their blocks to make room for prioritized sequences.

In the first implementations, vLLM would transfer evicted blocks to the CPU memory and swap them back to GPU to resume processing once memory is free again. The amount of CPU memory available for swapping depends on the --swap-space parameter value passed to the engine. When the entire swap space is consumed, evicted blocks are simply deleted, and re-computed when sequences are scheduled back. This recomputation is similar to the prefill-phase, as the initial prompt and already generated tokens may be considered as one larger prompt. So, it benefits from GPU parallelism for speed.

However, this behaviour was changed in vLLM V1. By default, blocks are not swapped to CPU anymore but are always recomputed. This is a choice from the team to limit transfers between CPU and GPU.

The number of CPU blocks is now set to 0 in vllm/v1/engine/core.py, so reproducing the previous behaviour would come at an extra cost: cloning the repository, changing the parameter in _initialize_kv_caches, and recompiling the project.

Conclusion

Although I went deeper in this post, there would still be much to say about vLLM. It is a fast-evolving framework and the release of V1 introduced many upgrades and changes in behaviours. I believe it is a great project that enables developers to serve LLMs with minimal latency, thus making possible to build a wider range of applications. To make it even better, Hugging Face has recently announced that all the models in the Hub can now be deployed with vLLM.

There are of course (fortunately even) alternatives like TGI and Triton+TensorRT-LLM which I previously mentionned. SGLang is another interesting serving framework for LLMs. It is a more recent project that introduces RadixAttention, another algorithm to optimize self attention during LLM inference.

There are also innovations on the hardware level. Companies like Groq and Cerebras, and even AWS, have introduced LLM-specific chips with very promising perspectives: Cerebras has reached up to 1100 token/s with mistral models.

Well that was a long post, thank you for reading it!